Minnesota River Valley Sites

The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 that raged through southwestern Minnesota was the result of failed U.S. government Indian policies. It continues to impact the lives of many communities to this day. Uncover the places and stories that changed the course of history along the Minnesota River Valley.

“This is our ancient homeland, the birthplace of the Dakota people.”

Dr. Clifford Canku, Sisseton Wahpeton, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

Birch Coulee Battlefield

Originally called Tanpa (birch) in Dakota, Birch Coulee is a creek that flows into the Minnesota River. One of the hardest-fought battles of the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 took place nearby. Hear reflections on the spiritual connection Dakota people have with the land and their fight for survival.

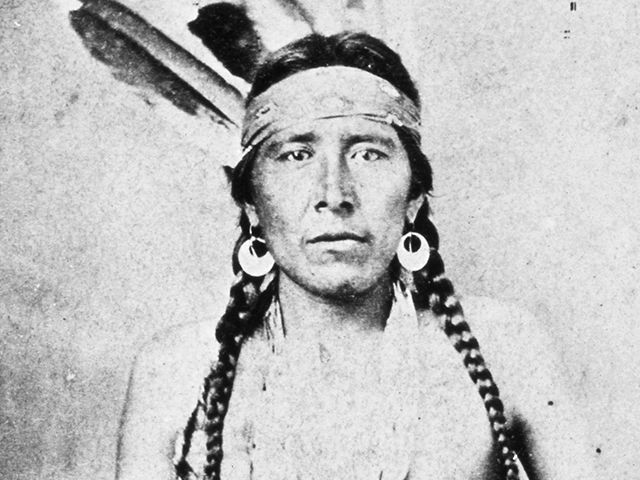

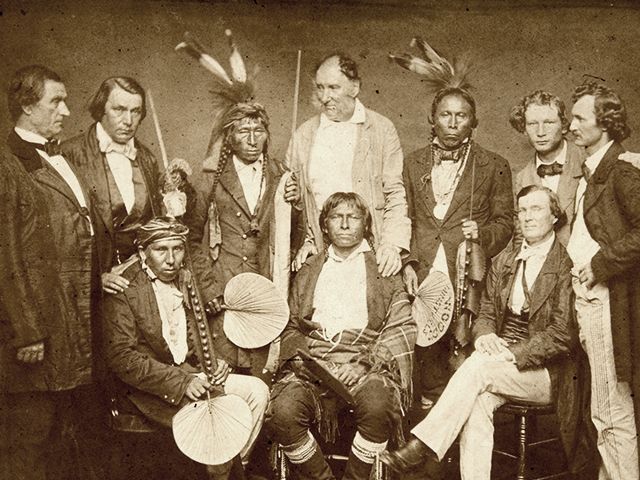

Big Eagle, leader in the U.S.- Dakota War. 1863, MNHS Collections

Big Eagle, leader in the U.S.- Dakota War. 1863, MNHS Collections

Stories and Reflections

On Sept. 2, 1862, Dakota soldiers attacked a burial party sent by Col. Henry Sibley. The Dakota kept U.S. soldiers under siege for 36 hours before a relief detachment arrived from Fort Ridgely.

Additional Resources

Visit Birch Coulee Battlefield

- Birch Coulee Historic Site Tour the self-guided site with markers explaining the battle from Dakota and U.S. soldiers’ perspectives.

Camp Release

Camp Release marks the site where some Dakota leaders looking for a peaceful resolution, including Maza Sa (Chief Red Iron), released captives they protected during the battle of Woodlake in the Fall of 1862. Hear the story of Mazasa and learn about the mounting tensions among the Dakota leading up to the war.

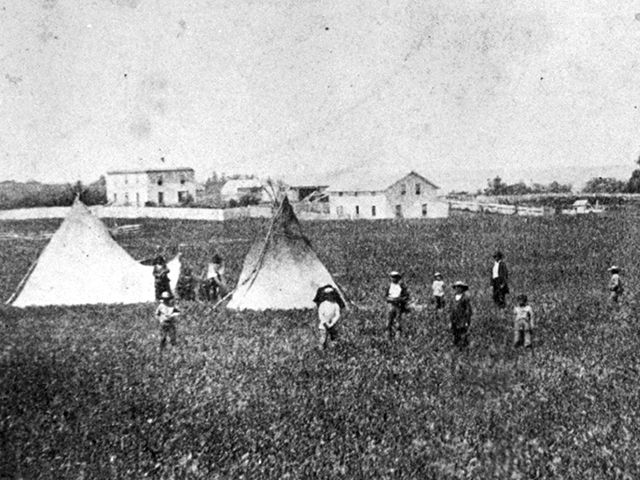

Camp Release 1862, MNHS Collections

Camp Release 1862, MNHS Collections

“I just try to imagine what it would have been like to be there.... The Indians [must have been] realizing: ‘This is over. What’s our next step?’”

—Terry Sveine, New Ulm Settler Descendant, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

In late September, after the defeat of Little Crow’s forces, a group of Dakota chiefs released white and mixed-race captives to Col. Henry Sibley. He then moved the captives to his own encampment near Montevideo, which came to be known as Camp Release. Sibley also took into custody about 1,200 Dakota, a number that grew to nearly 2,000 as more surrendered or were captured. The trials of the Dakota who took part in the war began at Sibley’s Camp Release headquarters on September 28, 1862. Sibley later moved his troops and the prisoners to the Lower Sioux Agency, where the trials continued.

Additional Resources

Fort Renville

Although Fort Renville no longer exists, at one time the site boasted a large fur-trading post built in 1826 by French-Dakota trader Joseph Renville. Learn about Dakota life before the arrival of Europeans and the changes the fur trade brought to Minnesota.

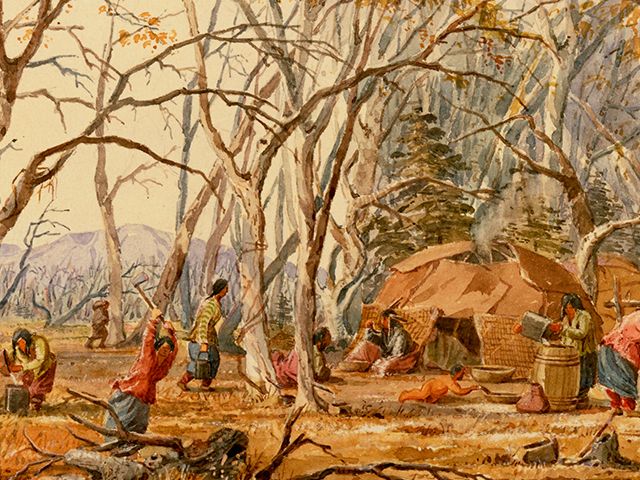

Indian Sugar Camp. Watercolor by Seth Eastman, ca. 1850, MNHS Collections

Indian Sugar Camp. Watercolor by Seth Eastman, ca. 1850, MNHS Collections

“The Dakota people were here long before the European contact...we lived off the land, we were nomadic.... There was life that went on here.”

—Grace Goldtooth, Lower Sioux

Stories and Reflections

The fur trade existed in Minnesota for 200 years and marked the beginning of Dakota and European contact. French-Dakota trader Joseph Renville was influential in Dakota-European relations and in 1835 he invited missionaries to start the Lac qui Parle Mission nearby.

Additional Resources

Visit Fort Renville

- Fort Renville was located in what is now Lac qui Parle State Park

Fort Ridgely

Built in 1853, Fort Ridgely was originally designed as a law enforcement center to keep peace as European settlers poured into the ceded Dakota lands. Learn about archaeological findings at Fort Ridgely and hear Dakota people reflect on the site today.

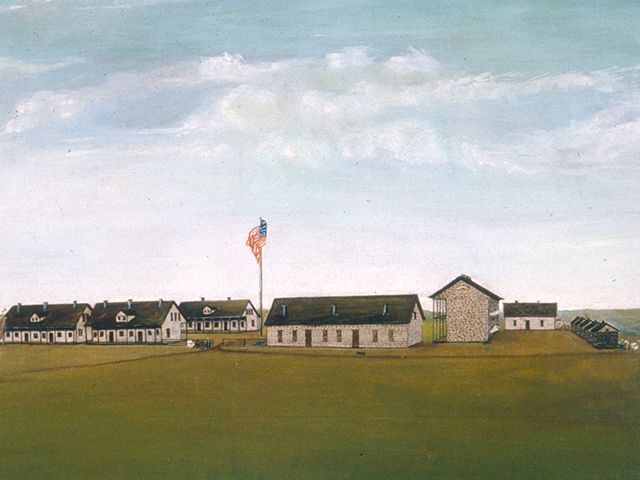

Fort Ridgely. Painting by James McGrew, 1890, MNHS Collections

Fort Ridgely. Painting by James McGrew, 1890, MNHS Collections

Stories and Reflections

While built in 1853, by 1862 Fort Ridgely was a training base for Civil War volunteers. The military outpost also saw combat during the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

Dakota forces attacked the fort twice — on August 20 and 22, 1862. The fort suddenly became one of the few military bases west of the Mississippi to withstand a direct assault. Fort Ridgely’s 280 military and civilian defenders held out until U.S. Army reinforcements ended the siege.

Additional Resources

Visit Fort Ridgely

- Located in Fort Ridgely State Park and managed by Nicollet County Historical Society. Visitors to the Fort Ridgely Historic Site can see the ruins of this once thriving outpost and learn more about its role in the U.S.-Dakota War. A Visit to the adjacent Fort Ridgely Cemetery offers more history.

Henderson

After the war, nearly 1,700 Dakota people were forced to march to Fort Snelling from Henderson. Learn more about the march and how it is commemorated today.

xxxxx. credit

Stories and Reflections

After the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, nearly 1,700 Dakota women, children and elders were forced to travel for six days to an internment camp at Fort Snelling. As they marched through Henderson and nearby towns, angry residents threatened and attacked the captive Dakota.

Additional Resources

Lac qui Parle Mission

The first Dakota-language dictionary was completed at the Lac qui Parle mission, founded in 1835. Learn about the mission, American Indian boarding schools and efforts to revive the Dakota language.

Lac qui Parle Mission. 1960, MNHS Collections

Lac qui Parle Mission. 1960, MNHS Collections

Stories and Reflections

The Lac qui Parle Mission was one of the first churches and schools in Minnesota. It was built by missionaries at a trading post founded by explorer and fur trader Joseph Renville.

Additional Resources

Visit Lac qui Parle Mission

- Lac qui Parle Historic Site is located in Lac qui Parle State Park and is managed by Chippewa County Historical Society. The site features artifacts and exhibits related to Dakota people and the missionaries who worked with them. See what life was like at a pre-territorial mission.

Mahkato / Mankato

Mahkato (Mankato) means “Blue Earth” in Dakota and is a city located on the Minnesota river. At the end of the U.S.-Dakota War, 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato on December 26, 1862 in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. Learn about the legacy of the Mankato hangings and how their effects are still felt today.

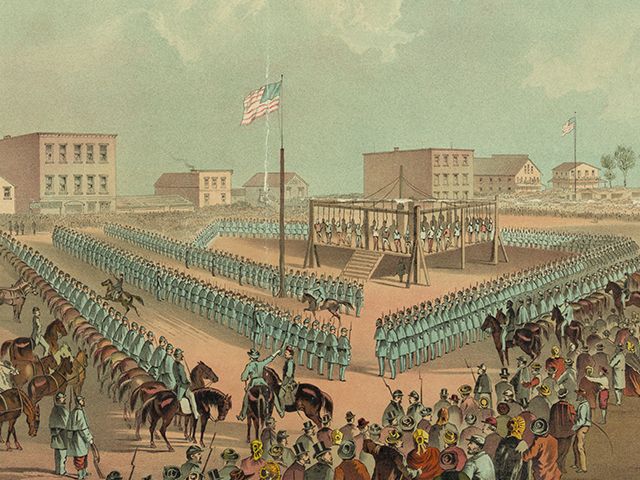

Execution of the 38 Dakota at Mankato, Minnesota, December 26, 1862. Hayes Litho[graph] Company ca. 1863 - 1875, MNHS Collections

Execution of the 38 Dakota at Mankato, Minnesota, December 26, 1862. Hayes Litho[graph] Company ca. 1863 - 1875, MNHS Collections

“There are descendants there, still living in Mankato from 1862. I met a woman there who is the granddaughter of the man that cut that rope, and she met us there at the hanging site and we just held each other and cried. It was very healing for her, and for me also.”

—Pamela Halverson, Lower Sioux, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

Of the hundreds of Dakota people who surrendered or were captured during the U.S.-Dakota War, 303 men were convicted in a military court. At the urging of Bishop Henry Whipple, President Abraham Lincoln reviewed the convictions and commuted the sentences of 264 to prison terms. Lincoln then signed the order condemning 39 men to death by hanging.

One prisoner was granted a reprieve just before the sentencing was carried out. The remaining 38 men were hanged at Mankato on December 26, 1862 — the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

Additional Resources

- Trials & Hanging at Mankato

- Forced Marches & Imprisonment

- Commemoration Today

- Image: Prison

- Image: Hangings at Mankato

Visit Mankato

- Reconciliation Park. On the site of the execution, this park was built through a collaboration of the Dakota and Mankato communities.

- The Blue Earth County Heritage Center preserves, displays and celebrates Dakota culture.

Maya Kicaksa / New Ulm

Founded in the 1850s on Dakota homeland, the town of New Ulm was a destination for German immigrants on the prairie. Clashes over land rights and unfulfilled promises led to tension between the Dakota and these new arrivals. Hear descriptions of European immigrant life and the legacy 1862 left with the people of New Ulm.

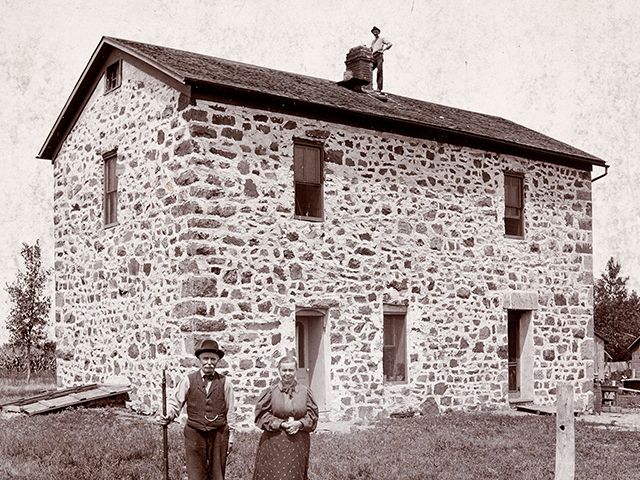

Homesteading Family 1886, National Archives and Records Administration

Homesteading Family 1886, National Archives and Records Administration

“New Ulm basically became a ghost town.”

- Robert Beussman, New Ulm Settler Descendant, Oral History Project Participant

Stories and Reflections

New Ulm was the site of two attacks by the Dakota — on August 19 and 23, 1862. Using outlying buildings for cover, the Dakota fired on the town’s defenders and burned buildings near the river, leaving more than a third of the town in ruins.

With little food and ammunition left in New Ulm and fearful of another attack, about 2,000 residents fled to Mankato, St. Peter and St. Paul. New Ulm settlers began returning in early September. In December 1862, the town officially reorganized. Today, monuments and memorials commemorate the attacks.

Additional Resources

- The Attacks on New Ulm

- Image: New Ulm, 1860

- Image: New Ulm Attack

- Settlers

- Stories from settler descendants

Visit New Ulm

- Brown County Historical Society Museum exhibit: “Never Shall I Forget - Brown County and the U.S.-Dakota War”

- Frederick W. Kiesling Haus One of few structures that survived the war.

- Harkin Store Historic Site provides a glimpse of settler life after the war, with period wares still on the shelves.

Oiyuwege / Traverse des Sioux

The Minnesota River crossing of Traverse des Sioux is the site of the 1851 U.S.-Dakota land treaty. Listen to perspectives on the treaty signings of 1851 and 1858 and their lasting impact.

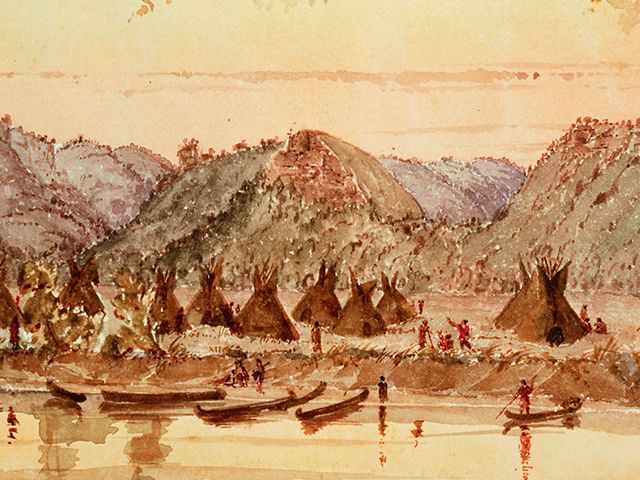

Camp at Traverse des Sioux, 1851, MNHS Collections

Camp at Traverse des Sioux, 1851, MNHS Collections

“The Indians wanted to live as they did before the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux— go where they pleased...hunt game wherever they could find it, sell their furs to the traders and live as they could.”

—Wanbditanka (Big Eagle), Mdewakanton, 1894

Stories and Reflections

A shallow river crossing, Traverse des Sioux was a gathering place for thousands of years. When European settlers first came to Minnesota, they traded information and ideas here with Dakota hunters. It was also the site of the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux where the upper bands of the Dakota nation ceded about half of present-day Minnesota to the U.S. government in exchange for promises of cash, goods, education and a reservation.

Additional Resources:

- Traverse des Sioux Historic Site

- Glossary: Traverse des Sioux

- Image: Camp at Traverse des Sioux

- Image: Treaty of Traverse des Sioux

- Image: Treaty of Traverse des Sioux Traders’ Papers

- What’s in a Treaty? Treaty of Traverse des Sioux document

Visit St. Peter

- The Treaty Site History Center provides information about treaties, the fur trade and Dakota culture.

Pezihutazizi Oyate /

Upper Sioux Agency

The Upper Sioux Dakota community was forced to leave their home along the Minnesota River or killed after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Hear reflections on the values and enduring strength of the Dakota people.

Hazelwood Mission station of Reverend Stephen R. Riggs, Yellow Medicine County. 1860, MNHS Collections

Hazelwood Mission station of Reverend Stephen R. Riggs, Yellow Medicine County. 1860, MNHS Collections

“Families were torn apart. I just wonder how my relatives made it through all of that, how difficult a time that had to have been, to be able to survive.”

—Lavonne Swenson, Lower Sioux, Oral History Project

Stories and Reflections

The Upper Sioux or Yellow Medicine Agency was established in 1854 as a U.S. government administrative center for the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of Dakota. Most of the agency’s buildings were destroyed in the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. One structure, the agency house, has been reconstructed to its pre-1862 condition and the foundations of other buildings are marked. In 1938, 746 acres of the area were returned to the tribe.

Additional Resources

- Image Dakota Women Winnowing Wheat, Upper Agency

- Upper Sioux Community Stories

- Different Lifeways Collide

Visit Upper Sioux Agency

- Upper Sioux Agency State Park preserves the site of the Upper Sioux Agency and includes 18 miles of trails around the Yellow Medicine River Valley.

Village of Caŋsayapi

/

Lower Sioux Agency

The village of Caŋsayapi, known today as the Lower Sioux Agency, was one of two Indian agencies established to be the administrative centers of Dakota reservations resulting from the Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota. Gain insights into the Dakota people’s connection to land and home along the Minnesota River Valley and how the war changed this.

Lower Sioux Agency building. Photograph by Edward Augustus Bromley, 1897, MNHS Collections

Lower Sioux Agency building. Photograph by Edward Augustus Bromley, 1897, MNHS Collections

“I’m standing in a place where my ancestors were... and I wonder what they were thinking when they were here...? It gives me comfort to know that they stood right here.”

—Sandra Geshick, Lower Sioux, Oral History Project

Stories and Reflections

The Lower Sioux Agency was a U.S. government administrative center for the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands of Dakota. In the months leading up to the war, the U.S. government failed to make annuity payments owed to the Dakota and refused to provide food and supplies. These actions contributed to the growing resentment that led to the war in the summer of 1862. As tensions mounted, a reluctant Taoyateduta (Little Crow) led an attack on the Lower Sioux Agency on August 18, 1862, killing 18 traders and government employees. The Dakota then attacked settlements along the Minnesota River Valley, in a strategic effort to reclaim their homeland, killing white settlers and compelling thousands to flee.

Visit Lower Sioux Agency

- Lower Sioux Agency Historic Site: The Minnesota Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the Lower Sioux Indian Community, which manages this site. Includes exhibits on Dakota history, life and culture and self-guided trails to explore the landscape and the warehouse building.

Wabasa / Wabasha Village

Chief Wabasa (Wabasha) was a leader of the Mdewakanton band of Dakota. His community originally lived along the lower Mississippi River around Winona, Minnesota. But Chief Wabasa moved seasonally as far north as Fort Snelling. Learn about early Dakota villages and the role of chiefs in community life.

Wah-ba-sha Village on the Mississippi River. Watercolor by Seth Eastman, ca. 1845, MNHS Collections

Wah-ba-sha Village on the Mississippi River. Watercolor by Seth Eastman, ca. 1845, MNHS Collections

“You have said you are sorry to see my young men engaged still in their foolish dances. I am sorry.... It is because their hearts are sick. They don’t know whether these lands are to be their home or not.”

—Chief Wabasa to Bishop Henry Whipple

Stories and Reflections

After the Treaty of 1851, Chief Wabasa moved his people to the newly formed reservation and lived in small villages along the Minnesota River. A marker near Morton identifies where Wabasa’s band moved in 1853 after ceding millions of acres to the U.S. government. Wabasa and his people were expelled from Minnesota, even though he had opposed the war.

Additional Resources