"Wakute was our band leader. Some of our relatives in the Canku family were captured in 1862 and sent to Fort Snelling. There was nine of our family that were sent there. And then the rest escaped and went to the Plains. They were implicated for being Dakota. Just being Dakota means that you were guilty before any consideration of being innocent."

"Wakute was our band leader. Some of our relatives in the Canku family were captured in 1862 and sent to Fort Snelling. There was nine of our family that were sent there. And then the rest escaped and went to the Plains. They were implicated for being Dakota. Just being Dakota means that you were guilty before any consideration of being innocent."

Dr. Clifford Canku, Sisseton Wahpeton community of Dakota, 2010

Of the more than 600 white people killed during the war, just over 70 were soldiers, and about 50 more were armed civilians. The others were unarmed civilians--mostly young men, women, and children who were recent immigrants to Minnesota. Historian Curtis Dahlin, who has extracted figures from public and cemetery records as well as from media reports, estimates that 30 per cent of the civilians killed were children aged ten and under. Another 40 per cent were adults between the ages of 20 and 40.

Historians have names for 32 of the estimated 75-100 Dakota soldiers who died during the war (and before the executions on December 26). These names have been gleaned primarily from the testimony of Dakota eyewitnesses.

More than one-quarter of the Dakota people who surrendered in 1862 died during the following year.

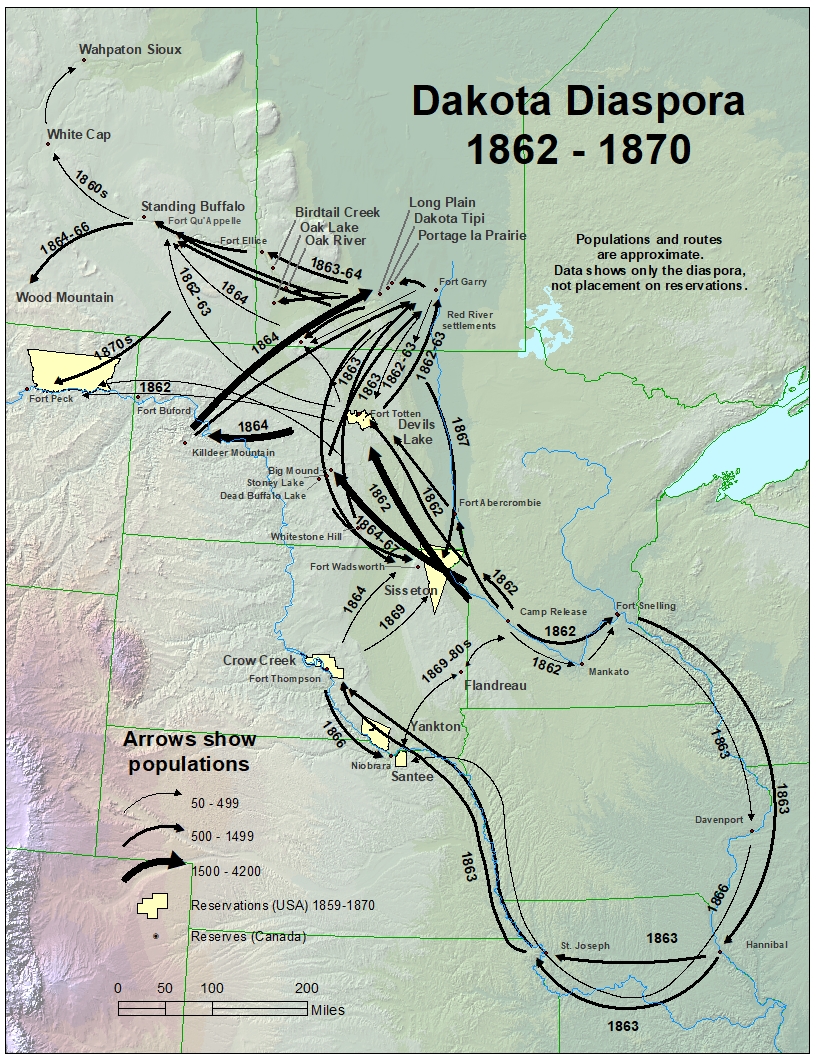

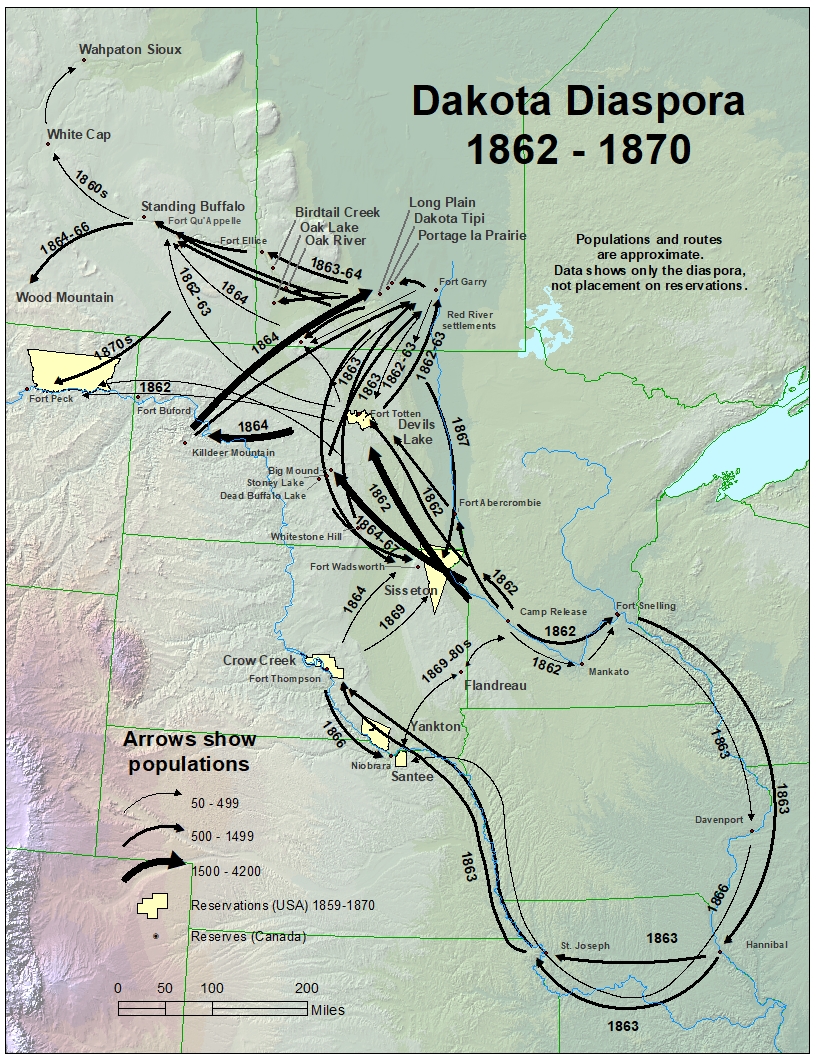

After their exile from Minnesota, the Dakota faced concentration onto reservations, pressure to assimilate, and opening of reservation land for white settlement.

Dakota communities outside Minnesota were concentrated in several major areas: reservations created at Santee, Nebraska (1869); Sisseton and Devil’s Lake, North Dakota (established by treaty in 1867); as well as reserves in Manitoba and Saskatchewan (throughout the 1870s). A small group of families left the reservation at Santee and formed a community in the Big Sioux river valley in Flandreau, South Dakota, in 1869. Another group left the Sisseton Reservation and settled at Brown Earth, South Dakota, in 1874. A reservation established in 1866 at Fort Peck, Montana, also drew exiles from Minnesota.

A small number of Dakota people remained in Minnesota after the war. In the 1880s, more began to return from exile. Several families purchased land that eventually became the Lower Sioux community. In 1887 some Sissetons settled near Granite Falls; in 1910 they were joined by some Mdewakantons and Yanktons, forming the basis for today’s Upper Sioux community. Other communities eventually developed at Prairie Island and Shakopee.

Letter From Gen. John Pope to Henry Sibley, September 28, 1862:

"The horrible massacres of women and children and the outrageous abuse of female prisoners, still alive, call for punishment beyond human power to inflict. There will be no peace in this region by virtue of treaties and Indian faith. It is my purpose utterly to exterminate the Sioux if I have the power to do so and even if it requires a campaign lasting the whole of next year. Destroy everything belonging to them and force them out to the plains, unless, as I suggest, you can capture them. They are to be treated as maniacs or wild beasts, and by no means as people with whom treaties or compromises can be made."

"Wakute was our band leader. Some of our relatives in the Canku family were captured in 1862 and sent to Fort Snelling. There was nine of our family that were sent there. And then the rest escaped and went to the Plains. They were implicated for being Dakota. Just being Dakota means that you were guilty before any consideration of being innocent."

"Wakute was our band leader. Some of our relatives in the Canku family were captured in 1862 and sent to Fort Snelling. There was nine of our family that were sent there. And then the rest escaped and went to the Plains. They were implicated for being Dakota. Just being Dakota means that you were guilty before any consideration of being innocent."