"The nuns and the priests and the Indian agent; they came and they took me and my brother away in 1934. My mom, she tried to resist, but if you do that, you’re going to go to jail. And it happened to some other people there in my generation; some of the parents went to jail."

"The nuns and the priests and the Indian agent; they came and they took me and my brother away in 1934. My mom, she tried to resist, but if you do that, you’re going to go to jail. And it happened to some other people there in my generation; some of the parents went to jail."

Albert Taylor, Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, Manitoba, Canada

In the late eighteenth century, the U.S. government desired to acculturate and assimilate American Indians (as opposed to instituting reservations), and promoted the practice of education Indian children in the ways of white people. To aid this, the Civilization Fund Act of 1819 provided funding to societies (mostly religious) who worked on educating Indians, often at schools. Schools were founded by missionaries next to Indian settlements (and later reservations). As time went on schools were built with boarding facilities, to accommodate students who lived too far to attend on a daily basis.

U.S. Army officer Richard Henry Pratt founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1879, at a former military installation. It became a model for others established by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Pratt, who believed in "assimilation through total immersion" said in a speech in 1892:

"A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him and save the man."

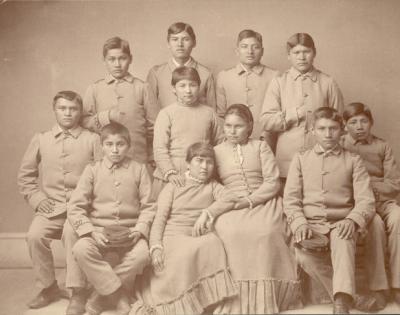

As the Carlisle model was more widely adopted by the U.S. government, and religious denominations continued opening schools, thousands of Indian children were often forcibly separated from their families and tribes and sent to boarding schools, sometimes far from their home reservations.

When they arrived at school, students were given English names, short haircuts, and uniforms. They were not allowed to speak their own languages, often facing punishment for doing so, and were forced to take on Christianity. Overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and infectious disease were common in many schools. Students often ran away in an effort to get home, and others died during their stay. In 1886 John B. Riley, Indian School Superintendent, said:

"Only by complete isolation of the Indian child from his savage antecedents can he be satisfactorily educated, and the extra expense attendant thereon is more than compensated by the thoroughness of the work."

While some Indians felt oppression and trauma from their boarding school experiences, others used the schools to their advantage and have positive memories. Indian peoples continue to remember and retell this history and seek to educate others about the variety of their experiences.

In Canada, the government made an official apology. Watch "Canada Apologizes for Residential School System."

To learn more, watch "An Overdue Apology", a project by the University of Minnesota Students.

Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1995.

Websites

Children and Youth in History. The Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University and the University of Missouri-Kansas City. 2008

Native Words Native Warriors. The National Museum of the American Indian.

Primary

The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 Oral History Project. Minnesota Historical Society.

Bear, Charla. American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many. National Public Radio, 2008.

Meriam, Lewis. The Problem of Indian Administration. The Institute for Government Research Studies in Administration. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1928.

National Museum of the American Indian

Secondary

Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1995.

Child, Brenda J. Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.